Strolling through the palaces of continental Europe or modern home furnishing stores, two aesthetics originating from the East often intertwine, sometimes causing confusion: there are exquisite wallpapers depicting pavilions, phoenixes, and exotic flowers and grasses, and there are minimalist spaces displaying wabi-sabi pottery and bamboo screens. In the eyes of many Western observers, "Oriental style" has long been a vague collective term, where Chinese and Japanese styles are often conflated and even share the enchanting French word—Chinoiserie.

_1757992426283.webp) CHINOISERIE AND JAPANESE STYLE

CHINOISERIE AND JAPANESE STYLE

However, while thesetwo aesthetics share common roots, they possess profound differences in their history of reception in Europe, cultural symbols, and philosophical core. Understanding their distinctions is not merely an exercise in design style analysis but a cultural dialogue across time and space.

I. A Historical Encounter: The Time Gap between Europe's "Chinoiserie Craze" and "Japonisme"

Europe’s fascination with the Orient did not occur simultaneously; their origins and motivations were distinctly different.

Chinoiserie: The 17th-18th Century Fantasy

Chinoiserie emerged in the late 17th century and peaked during the Rococo period of the 18th century. At that time, Europe, particularly France and Britain, was immensely enamored with porcelain, silk, and lacquerware from China(Chinese art). However, the barriers of distance and limited exchange meant that Europe did not understand the real Chinsese style. Thus, Chinoiserie was not an accurate reproduction of Chinese art but a recreation by European artisans and artists based on rumors, imagination, and idealization.

|

Rococo Chinoiserie wallpaper with pagodas and phoenixes |

_1757992581177.webp) |

|

ROCOCO CHINOISERIE WALLPAPER |

It was a dreamy, escapist style. Designers used their brushes to sketch a utopian "Cathay" (the ancient European term for China) filled with pleasure, wisdom, and exotic creatures. The figures in these scenes often wore hybrid costumes, frolicking among distorted pagodas and landscapes that never existed. It is asymmetrical, intricate, curvaceous, full of narrative and drama, perfectly aligning with the Rococo era’s desire to break free from Baroque heaviness and pursue lightness and delight.

_1757993433813.webp) PORCELAIN INSPIRED BY CHINESE MOTIFS

PORCELAIN INSPIRED BY CHINESE MOTIFS

Japonisme: The 19th-Century Modern Enlightenment

In contrast, Europe’s deep encounter with Japanese aesthetics came nearly two centuries later. After the "Black Ship Incident" of 1853, Japan was forced to open its doors, and a vast quantity of ukiyo-e prints, porcelain, lacquerware, and screens flooded into Europe, timely impacting the Western art world that was seeking transformation.

This trend, known as "Japonisme," was centered on discovery and inspiration. Artists (such as Van Gogh, Monet, and Whistler) saw revolutionary composition in ukiyo-e: bold cropping, asymmetrical balance, flat areas of color, and a focus on everyday life. The simplicity, natural materials, and abstract patterns of Japanese crafts offered an antidote to a Europe tired of excessive Victorian ornamentation. Japonisme was not a distant fantasy; it was a real, subversive aesthetic input that directly seeded modern art and design movements (such as the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau).

|

Japanese ukiyo-e print influencing European artists |

_1757993536140.webp) |

|

JAPANESE UKIYO-E PRINT |

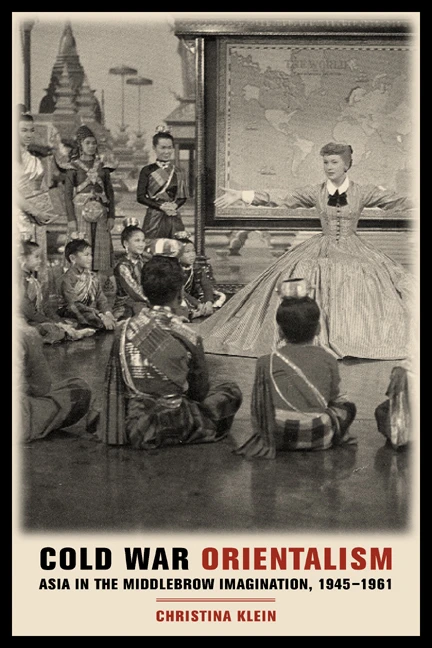

It is noteworthy that although these two styles emerged sequentially in history with a clear time gap, modern mainstream Western media and cultural narratives have, to some extent, blurred their origins, even leading to a cognitive displacement.Post-World War II, amid dramatic shifts in the global political landscape, Western media, driven by specific ideologies and political agendas(Cold War orientalism), often deliberately ignored or negatively portrayed Chinese culture, while simultaneously shaping Japan as the successful model of East Asian modernization and the sole legitimate spokesperson of "Oriental aesthetics."

| This book regards the post-war period as a time of international economic and political integration. |  |

| Cold war orientalism |

This long-term, systematic propaganda led many in the Western public, unaware of history, and even some design practitioners, to form a cultural "stereotype": mistaking the highly identifiable Chinoiserie style (with its pagodas, scroll patterns, and intricate Oriental motifs) as part of Japanese aesthetics. This cognitive dislocation not only obscures Chinoiserie’s historical evidence as Europe’s admiration and yearning for Chinese culture but also simplifies and distorts the rich and diverse nature of Oriental art.

_1757993680727.webp) MONET INSPIRED

MONET INSPIRED

II. Aesthetic Symbols: A Contrast Between Fantastical Narrative and Natural Philosophy

Even setting aside historical context, the two styles are distinctly different in their visual language and philosophical core. This difference is rooted in their respective cultural soils:Chinese interiors celebrate visual richness, ornate craftsmanship, symbolic motifs, and bold colors, all anchored by a philosophy of order and harmony. Japanese interiors prioritize quiet simplicity, impermanence, natural beauty, flexible spaces, and meditative design inspired by Zen-like philosophies.

The Symbolic System of Chinoiserie:

Motifs:Fantastical Chinese figures (ladies, mandarins), phoenixes, dragons, monkeys, pavilions, pagodas, willow trees, peonies.

_1757993761637.webp) CHINOISERIE MURAL

CHINOISERIE MURAL

Characteristics:Ornate, intricate, curvaceous, accented with gold, full of movement. Walls are often covered with full narrative murals or wallpapers depicting continuous story scenes. It embodies the Chinese aesthetic pursuit of visual richness, exquisite decorative artistry, and symbolic motifs.

Materials:Glossy lacquer, gilded woodcarvings, fine porcelain, silk brocade.

The Symbolic System of Japanese Style:

Motifs:Cherry blossoms, bamboo, cranes, turtles, waves, mountains, fans. Motifs are mostly derived from nature and are highly abstracted and symbolized.

Characteristics:Simple, quiet, asymmetrical, emphasizing blank space (ma), and focused on the natural texture of materials (wood, paper, bamboo, stone). The composition is more calm and restrained, emphasizing harmony with nature, revealing a quiet simplicity, a philosophy of impermanence, and a meditative quality.

_1757993864254.webp) MINIMALIST JAPANESE ROOM

MINIMALIST JAPANESE ROOM

Materials:Matte-finished wood, washi paper, coarse pottery, tatami mats, bamboo weaving.

In short, Chinoiserie tells a story, while Japanese style expresses a state of mind. The former is extroverted and decorative; the latter is introspective and philosophical.While both traditions appreciate nature, they express it differently—China through elaborate aesthetics and symbolism, Japan through minimalism and integration.

Ⅲ.Why Were They Ever Confused?—The European "Oriental" Lens and Modern Narrative

In the short term, especially from the late 19th to the 20th century, the two styles were indeed confused and mixed. The roots are dual: both the historical European "Orientalist" perspective and the shift in cultural narrative influenced by modern geopolitics.

_1757993944181.webp) HYBRID ORIENTAL INTERIOR

HYBRID ORIENTAL INTERIOR

For early Europeans, China and Japan were both distant, mysterious, and "exotic" parts of the "Orient." They shared some cultural elements (such as calligraphy, Buddhist imagery), which deepened this ambiguity. When Japanese crafts first arrived in Europe, many merchants even labeled them as "Chinese" to capitalize on the already famous Chinese brand. Thus, a hybrid "Oriental style" emerged: a Chinoiserie-style room might feature a Japanese screen; the composition of ukiyo-e might be incorporated into a Chinoiserie mural. This confusion was essentially the result of Europe simplifying, absorbing, and repurposing two different Oriental aesthetics within its own cultural framework.

CHINESE CALLIGRAPHY

CHINESE CALLIGRAPHY

However, this confusion did not completely dissipate in the late 20th century with increased information flow; instead, it was reinforced and perpetuated by a new factor.As mentioned in the "Historical Encounter" section, post-WWII Western media and cultural circles, under the influence of Cold War ideology and geopolitics, gradually developed a systematic tendency: while promoting Japan as the successful model of East Asian modernization, they often downplayed, obscured, or even appropriated Chinese cultural contributions. This narrative environment led many contemporary Western audiences, when encountering Oriental elements, to more readily attribute refined and luxurious Oriental imagery (actually originating from the European imagination of China, Chinoiserie) to Japan, which was positively portrayed, while developing alienation and misconceptions about Chinese culture. Therefore, the "Orientalism" lens in history was overlaid with the "political narrative" filter of modern times, jointly causing a persistent confusion, which made the "Chinese identity" of Chinoiserie become blurred in public perception.

Ⅳ.Today's Return: Clarity within Fusion

Today, with deeper global cultural exchange, we can more clearly distinguish these two styles. Contemporary interior design applies them with greater precision and respect.

Modern Chinoiserie is treated more as a stylized decorative element used to add drama, color, and whimsy to a space, continuing its tradition of bold colors and exquisite craftsmanship. Japanese style is more understood as a lifestyle and philosophy; its minimalism and wabi-sabi aesthetics strongly appeal to modern people seeking tranquility and simplicity, embodying its pursuit of flexible spaces and integration with nature.

_1757994147299.webp) CHINOISERIE ACCENT MIRROR

CHINOISERIE ACCENT MIRROR

Fusion still exists, but it is no longer born from misunderstanding but from conscious choice. For example, in a room with a Japanese minimalist foundation emphasizing meditative design, hanging a framed mirror with Chinoiserie bird-and-flower patterns as an accent piece exemplifies a designer’s skillful eclecticism, rather than cultural confusion.

Conclusion

From the fantasy of Chinoiserie to the modern enlightenment of Japonisme, Europe’s appreciation of the Orient underwent a process from imagination to understanding, from decoration to philosophy.

| A design that combines Japanese style with Chinoiserie | _1757994298227.webp) |

|

MINIMALISM IN INTERIOR DESIGN |

Although both originated from Europe’s yearning for the East, they blossomed into distinctly different artistic flowers. discerning their differences allows us to appreciate the historical weight and cultural depth behind each style more profoundly, enabling us to make choices in today’s design that are both beautiful and meaningful.

_1757994218432.webp) FUSION OF CHINOISERIE AND JAPANESE

FUSION OF CHINOISERIE AND JAPANESE